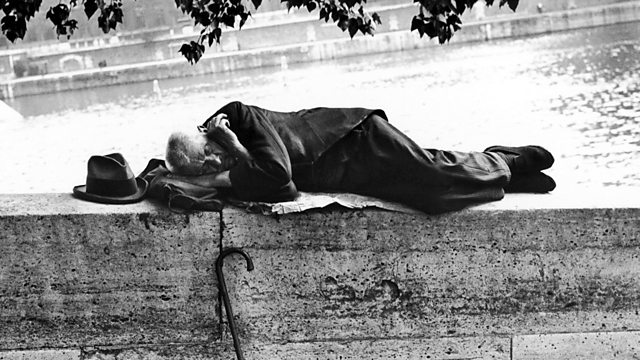

Down and Out

George Orwell’s eulogy to poverty

“And there is another feeling that is a great consolation in poverty. I believe everyone who has been hard up has experienced it. It is a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out. You have talked so often about going to the dogs — and well, here are the dogs, and you have reached them, and you can stand it. It takes off a lot of anxiety..“

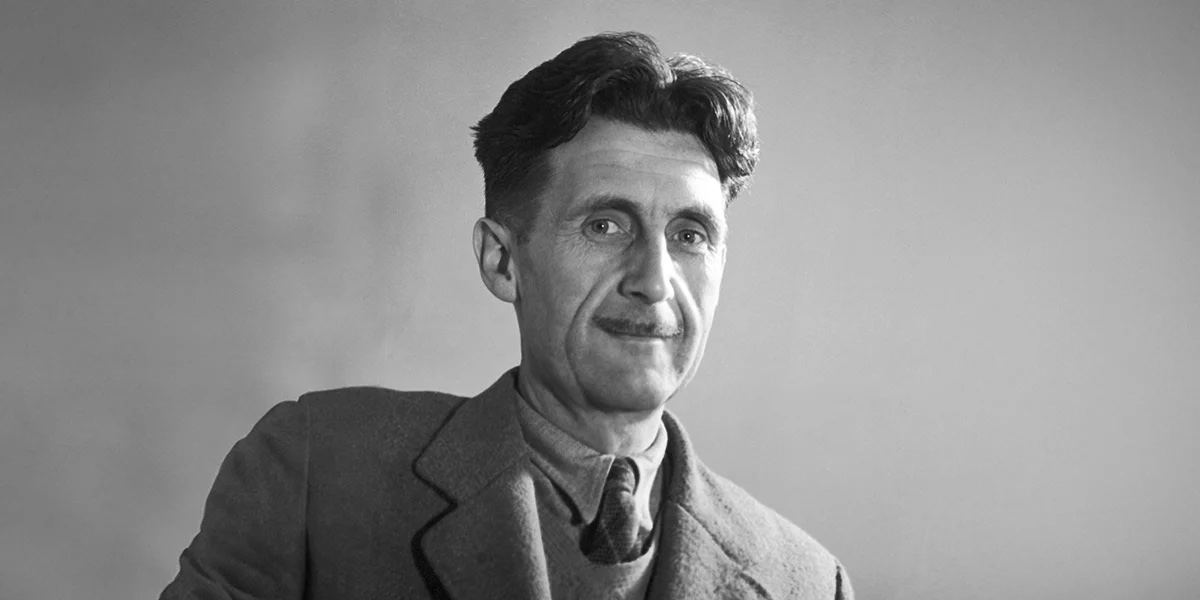

I recently picked up George Orwell's semi-autobiographical work, Down and Out in London and Paris, a book that catalogued a man deliberately throwing himself into the abyss of misfortune. And what a read!

Orwell, that most English of English writers, hurls himself into squalor with the eager curiosity of an anthropologist and the keen eye of an author who would become one of the most celebrated writers of our time within a decade of publishing this book.

Orwell left his post as a colonial police officer in Burma in search of becoming a writer, and like many writers of that era, he found himself in Paris.

But with no money.

![]()

Being down and out in Paris or London sounds grim, something I would never want to experience, yet reading Orwell's account makes me think: Damn, Orwell was punk rock af.

He came from what he described as the "upper lower middle class," which is to say that he had family prestige and history but not the money, making his voluntary descent into poverty all the more remarkable. His portrait of the destitute isn't painted with pity but with something approaching respect.

The broken men in Paris lodging houses and London spikes possess a certain ragged stoicism that speaks of the human spirit. They've been stripped of everything except their essential humanity, which might actually be the only thing you need to survive.

Orwell navigates this world with an almost perverse resourcefulness. When his clothes are stolen, when work disappears, when hunger sets in like a dull toothache, he responds not with despair but with improvised pragmatism. There's something quintessentially British in his ability to maintain standards while pawning his last decent shirt.

![]()

The genius of Down and Out isn't in its exposé of poverty, we've had centuries of those, but in its unflinching examination of how poverty strips away the decorative elements of personality until only character remains. Some men in the book are revealed as essentially hollow; others, like the indomitable Bozo, the pavement artist with a limp who still finds time to look up at the stars, demonstrates that dignity isn't a function of circumstance but of inner architecture.

Orwell emerged from his voluntary descent with a nuanced and bone-deep understanding that people are not defined by their conditions. The poor aren't saints or sinners; they're simply people with less money and fewer options.

Perhaps the perfect example of character comes near the end of the book, when a homeless man chases after Orwell to return a few cigarette ends, simply because Orwell had given him tobacco a few days earlier.

"A good turn deserves another" the man insists, smiling as he walks away.

I recently picked up George Orwell's semi-autobiographical work, Down and Out in London and Paris, a book that catalogued a man deliberately throwing himself into the abyss of misfortune. And what a read!

Orwell, that most English of English writers, hurls himself into squalor with the eager curiosity of an anthropologist and the keen eye of an author who would become one of the most celebrated writers of our time within a decade of publishing this book.

Orwell left his post as a colonial police officer in Burma in search of becoming a writer, and like many writers of that era, he found himself in Paris.

But with no money.

Being down and out in Paris or London sounds grim, something I would never want to experience, yet reading Orwell's account makes me think: Damn, Orwell was punk rock af.

He came from what he described as the "upper lower middle class," which is to say that he had family prestige and history but not the money, making his voluntary descent into poverty all the more remarkable. His portrait of the destitute isn't painted with pity but with something approaching respect.

The broken men in Paris lodging houses and London spikes possess a certain ragged stoicism that speaks of the human spirit. They've been stripped of everything except their essential humanity, which might actually be the only thing you need to survive.

Orwell navigates this world with an almost perverse resourcefulness. When his clothes are stolen, when work disappears, when hunger sets in like a dull toothache, he responds not with despair but with improvised pragmatism. There's something quintessentially British in his ability to maintain standards while pawning his last decent shirt.

The genius of Down and Out isn't in its exposé of poverty, we've had centuries of those, but in its unflinching examination of how poverty strips away the decorative elements of personality until only character remains. Some men in the book are revealed as essentially hollow; others, like the indomitable Bozo, the pavement artist with a limp who still finds time to look up at the stars, demonstrates that dignity isn't a function of circumstance but of inner architecture.

Orwell emerged from his voluntary descent with a nuanced and bone-deep understanding that people are not defined by their conditions. The poor aren't saints or sinners; they're simply people with less money and fewer options.

Perhaps the perfect example of character comes near the end of the book, when a homeless man chases after Orwell to return a few cigarette ends, simply because Orwell had given him tobacco a few days earlier.

"A good turn deserves another" the man insists, smiling as he walks away.

21 April 2025